"History has yet to impart all its lessons, and already are all the mistakes repeated."

The War on Terrorism Has Gone Cold

Note: Since this essay was written, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia have allowed their military facilities to be used by US forces, once the United Nations permit them to attack Iraq. Britain has pledged the strongest support for the US, despite many dissenters amongst the ranks of the ruling Labour Party. The United States Congress has passed a resolution approving the use of force to disarm Iraq.

|

Today, with the threat of communist

expansion long behind us, our national leaders are sounding battle cries

once more, rallying all defenders of liberty to face yet another menace. Our epic struggle at hand is the War on Terrorism, provoked by the grievous attacks of September 11th, 2001. The first campaign was to uproot al-Qaeda, the group responsible for the attacks. Operation Enduring Freedom overthrew the Taliban, the fundamentalist Islamic regime that hosted al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, but its leader Mullah Omar as well as Osama bin Laden, the head of the terrorist organization, had eluded capture. The next target, if the current US administration is to have its way, is Iraq, a potential user or dealer of weapons of mass destruction. Although Saddam Hussein's regime had indeed waged war with its ethnic minorities, its neighbors and the West during the past two decades, its connection with al-Qaeda or any other terrorist organization at any time is yet to be established. Even as the ashes settle in the Afghan

deserts, the gravity and breadth of the War on Terrorism grow by the day.

It is inevitably drawing comparison to the last great human conflict of

the twentieth century, the four-decade-long Cold War. |

||

|

Captured Soviet tanks in Afghanistan (Efrem Lukatsky, AP) While it may be forgivable to believe America had won and not merely outlasted the Cold War, it would be utterly wrong to think that, since then, America is beyond reproach in matters of war and peace. |

For all the spectacular successes and failures on both sides – the wars in Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Afghanistan and Angola, the split and reunification of Germany, the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis – it was not the United States and her Western allies that won, but the Soviet Union that lost. Communism, an untenable socio-economic model, was its own worst enemy. While it may be forgivable to believe that America had won and not merely outlasted the Cold War, it would be utterly wrong to think that, since then, America is beyond reproach in matters of war and peace. History has yet to impart all its lessons, and already are all the mistakes repeated. George W Bush could not put it any

more succinctly: "Either you're with us, or you're with the

terrorists." The War on Terrorism once again

divides the world into two camps, dismissing all cultural and historical

subtleties. In our zeal to fight communism during the McCarthy era, we

made little distinction between a North Korean and a North Vietnamese, let

alone the differences between a Russian, a Czech, an East German or even

an American communist. Does that make any more sense than labeling the

so-called Axis of Evil – Iraq, Iran and North Korea? |

|

|

Consider Pakistan. The current ruler, Pervez Musharaf, is a general who took over the country in a coup, arranged a special election he could not possibly lose to rubber-stamp his presidency, and rewrote the constitution to extend his powers. He did little to stop the repeated terrorist attacks against India over Kashmir, or the murders of Western nationals by Islamic extremists within Pakistan. He has nuclear weapons at his disposal. So why does the Bush administration not demand a "regime change" in Islamabad? As in the Cold War days, Washington is once again condoning despotism so long as its purpose is served. Musharaf pays lip service to America's War on Terrorism, giving Washington the impression that it has a strategic Muslim ally. The charade will not hold. Unless Musharaf makes good on his promise to restore democracy in Pakistan, his fate is likely that of his predecessors: exile, imprisonment, or assassination. Why didn't the US challenge Saddam Hussein back in the 1980s, when his Sunni regime used poison gas against the Kurds of northern Iraq, and the Shiites of southern Iraq and Iran? The Ayatollah Khomeni, whose followers spurned a secular absolute monarch the Americans supported, and held American citizens hostage for more than a year, was a greater foe at the time. Saddam was a friend not just because he was an enemy's enemy; he was selling oil, straight from one of the world's largest petroleum reserves under his sole control. |

||

|

Anti-US, anti-Israel protesters in Iran (Reuters) Let the historians decide whether American Cold War policy inadvertently kindled the fires of Islamic fundamentalism, by supporting such an unpopular despot in Tehran for so long. |

Only one thing remained amiss. Since the US

was providing Israel with the means of defense against her hostile Arab

neighbors, the Arab nations joined the Cold War, buying Kalashnikovs and

MiGs from their giant neighbor to the north. That was why Washington had

the Shah of Iran under its payroll in the first place, following its

sponsorship of the coup that overthrew the elected nationalist government

in 1953 – to contain the

spread of Soviet influence in the Muslim world. Let the historians decide

whether American Cold War policy inadvertently kindled the fires of

Islamic fundamentalism, by supporting such an unpopular despot in Tehran

for so long.

While Iran and Iraq were left alone by the rest of the world to slaughter each other, the USSR was pulling puppet strings in Kabul, and building bridges to bring in tanks from Uzbekistan. Fierce resistance came from those amongst the quarrelsome Afghan tribes rejecting and rejected by the cronies of Moscow; their holy war was too interesting for zealous Muslims of the Middle East and CIA operatives to stand idly by. Here, a young Saudi adventurer called Osama – learned, well connected, charismatic, and fabulously wealthy – began building a base for his private army. |

|

|

In hindsight, it is certain to say that the Kabul of the 1980s was doomed to fall, with or without American subversion. Had we seen our interests beyond the terms of the Cold War, we might have helped to rebuild impoverished Afghanistan right after the Russians left it in tatters, instead of abandoning it to local bandits and warlords, puritanical students trained in the madrasas of Pakistan, and fanatics from the Middle East and north Africa. That timely rehabilitation would necessitate the Afghan tribes to reconcile with their then-Soviet neighbors, so as to bring not just arms, but food, fuel, architects and civic engineers from north of their border. One decade later, the Berlin Wall came down, the dismantling of USSR and Yugoslavia was well underway, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and the Baltic states had petitioned to join the EU, apartheid was voted out of South Africa, and civilian governments were returning to Santiago and Buenos Aires. Forces that brought about the New World Order were greater than the designs of a single nation, but the graying Cold Warriors of America felt their victory was long overdue, their methods – selective containment, engagement or subversion of foreign regimes – well justified. Then Saddam invaded Kuwait. Indeed, the Gulf War of 1991-1992 was about the preservation of the Arabian Peninsula, the world's most important source of petroleum, but it was a little more than just that. If America and the West wanted only oil, we all could have simply pinched our noses and bought it from Saddam, as we have always done. |

||

|

US Special Forces in Afghanistan (Brennan Linsley, AP) We now shun wars in the traditional sense, preferring brief, limited "operations" with short-term objectives. |

What Saddam did was unacceptable for a world long accustomed to the duopoly of power during the Cold War. Baghdad seized the strategic initiative once privy only to Moscow and Washington – for falling out of line, US branded Iraq a “rogue state.” It even looked like an erstwhile superpower, rolling out its Soviet tanks, helicopters and phalanxes of Republican Guards armed with AK-47s. Its victim, Kuwait, was not a sworn blood enemy like Israel, or an immediate threat like Iran: it was a calculated target, a prey caught off guard. Iraq already had enough oil without the fields in Kuwait, but by claiming its new province, Saddam instilled a false sense of manifest destiny in his long-suffering people, thereby justifying his despotic rule. By then, the stakes of war were already quite high. It is only the poor, struggling peoples, crudely and cheaply armed, that fight for their long, tortuous causes, resorting to wars of attrition because they already have so little to lose. Modern military forces are given, in peacetime, ever more costly arms of bewildering sophistication, and trained to use them at ever-greater expense. Ironically, this heavy investment, affordable only to the most prosperous nations whose citizens covet their high standard of life, makes it far less likely for these nations to commit themselves to a long-drawn, high-casualty conflict. We now shun wars in the traditional sense, preferring brief, limited "operations" with short-term objectives. |

|

|

Ideally, it was how every battle in

the Cold War ought to be fought, when it came to fighting. The goal was

not to occupy every other nation on earth, but to apply enough force to

bend its will closer to one’s own. The coalition had these objectives:

field-testing America’s peerless weapon technology, securing the

West’s all-important oil supply, proving that Western and Muslim forces

could fight side by side against a common threat, and yes, liberating

Kuwait, which in itself was certainly not a bad thing. Operation Desert Storm came and went,

as fleeting as the flight of a stealth bomber. It met its objectives on

schedule, under budget (such as it was), with casualties and collateral

damage kept to a minimum. At the time, it did appear Saddam was put in his

proper place. American and British fighter pilots enforced no-fly zones

over the Kurdish and Shiite regions of northern and southern Iraq. UN

inspectors began checking Iraq’s capability of producing chemical,

biological and nuclear weapons, at least for a short while. Saddam himself

was left alone for the local opposition to topple him, or so his enemies

had hoped. Let history thus proclaim that the Gulf War was justified and successful: the same could not be said for so many wars in this lifetime. Yes, Saddam was spared, but the prospect of going after him, entrenched in his many bunkers, shielded by urban residents and hardened by the cause of defending the motherland, would be as daunting then as it is now. |

||

|

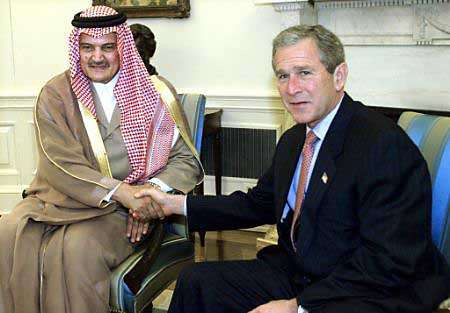

Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud al Faisal and US President George W Bush (Kevin Lamarque, Reuters) Every Arab nation, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain and even Kuwait, is refusing to participate in Gulf War II. |

So, what did America do

with such a bona fide victory? Disregarding local sensitivities,

the US left her warships, jets and troops in Saudi Arabia – Islam’s

most sacred grounds – believing that their stay was well earned, and

that their mere presence could impose parity and influence. A Cuban-style

trade embargo was imposed upon Iraq, impoverishing the country as a whole

while Saddam continued to sell his oil. There was no direct rapprochement

to Saddam, no attempt to bring him back to the international fold through

diplomatic persuasion.

It is telling that the current US

administration stands very much alone in its intention to bring the War on

Terrorism to Baghdad. Every Arab nation, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar,

Bahrain and even Kuwait, is

refusing to participate in Gulf War II. The sentiment throughout Europe is

the same. Russia and France, whose business interests in Iraq were

disrupted by the economic sanctions, lobbied to end them. In

Germany, Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder made "no war in Iraq" an

election slogan. Even Britain, the only other remaining coalition member

still patrolling the skies of Iraq, is noncommittal, insisting only upon

the return of UN weapon inspectors to Iraq. Such dissent in NATO,

which now counts Russia as a junior partner, was unthinkable during the

Cold War. |

|

|

Why was the precious dividend of the

Gulf War so completely spent? True, the Gulf States feared that a

protracted campaign to oust Saddam could permanently destabilize the

Arabian Peninsula, killing and displacing thousands of civillians. The Europeans were wary of another war, now that they

finally have the situation in the Balkans under control. The most

compelling reason, though, was coming from the Holy Land. In 2000, Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat failed to reach a peace agreement at Camp David, in effect nullifying the Oslo Peace Accord of 1993. The Palestinians, seething at the lack of progress towards statehood and restitution, needed only the slightest of Israeli provocation to renew their uprising. It happened when Likud PM candidate Ariel Sharon – the former general responsible for the massacre of Palestinian refugees in south Lebanon, and advocate for expansion of Jewish settlements in occupied Palestinian territories – paid a brief visit to the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem. (Loathe were the Arabs to see their enemy at the ruins of Solomon’s Temple, upon which the Prophet ascended to heaven, commemorated henceforth by the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque.) First came the hand-thrown stones, then sniper bullets, mortar shells and shrapnel-packed C4 strapped onto suicide bombers. The Israelis responded to such barbarity in kind, with tanks, missiles, assassinations of Palestinian leaders, razing of Palestinian towns, and votes for Sharon. |

||

|

"Colombo" actor Peter Falk witnessed a grenade attack in Rome in 1985, attributed to Abu Nidal (Quinto, AP) The moment terrorists began taking down airports and landmarks, they were bestowed the mythic status of a nefarious empire capable of world domination -- something right out of a James Bond movie. |

Back in the height of the Cold War, the two

superpowers did exploit the conflict between Israel and her Arab

neighbors. The US supplied arms to the Jewish State since her very

founding, and the USSR did so for the Arabs. (France, a Western nation

with a special affinity towards Arab society due to her former

colonization of north Africa, dealt with both sides.) Yet events

concerning the Middle East were soon moving away from the bipolar paradigm

well before the end of the Cold War itself. Manachem Begin and Anwar Sadat

made their peace at Camp David in 1978, the first peace agreement between

Israel and an Arab nation. Since then, Washington was obliged to provide

generous financial aid to Egypt to maintain Cairo’s moderate stance

towards the West; it gave the same consideration to Jordan several years

later. Relations between Moscow and Jerusalem have been warm since the

1980s, when Russian Jews started migrating en masse to Israel,

significantly altering the Knesset’s electoral base.

Missed opportunities abounded. The

various tenants of the White House, for all the friends they were making

in the Arab world, could not stoop to support the Palestinian cause. The

Arabs, resentful of Israel’s perennial dominance courtesy of American

largesse, chose to hate America as the Great Satan, as opposed to appeal

for a positive change in American public opinion. The lynchpin in all this

was and remains a single word: terrorism. The Americans shunned the

Palestinians because some of them resorted to hijacking planes, killing

Israeli athletes at the Olympics and car-bombing public buildings. The

Palestinians and their sympathizers believed they had the right to resist

Israeli occupation by force, which to some meant attacks against any

civilian target that could be associated with Israel and her Western

allies. Aside from the insidious pleasure of

seeing some fellow Arabs playing David against the American Goliath,

inflicting massive casualties within US borders (something that had not

been done by foreigners since December 6, 1941 at Pearl Harbor), would any

Arab or Muslim society ever benefit from the 9/11 attacks? Would the West

be thus coerced to do its bidding? The answer will always be a resounding

NO – and the terrorists know it, too. Yet they thrive on the premise

that, the bigger their attacks get, the more likely their victims may give

them more than their due. The moment terrorists began taking down airports

and landmarks, they were bestowed the

mythic status of a nefarious empire capable of world domination --

something right out of a James Bond movie. |

|

|

If that view seems grotesque and absurd, it is nevertheless a shadow of the paranoia the West and the Communist East felt towards each other for their apparent expansion. The Soviets moved into Poland, East Germany, the Baltic States and half of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, laying down a cordon sanitaire to preserve their communist order. Ho Chi Minh, a student of Marxism in Paris, brought communism to French Indochina as the Vietnamese were fighting their French overlords; the West responded by pushing the UN to divide Vietnam into two countries, one led by Minh in Hanoi and another, a proxy of Western interests in Saigon. Therefore, while the Viet Cong of North Vietnam thought they were resisting yet another colonial power to restore their nation, the administrations of Eisenhower, Kennedy and especially Johnson believed they were containing a "contagion" of communist regimes that were to merge with Red China, and spread all over southeast Asia. Thus, during the Cold War, proponents

of communism nearly always enjoyed an aura of sovereign power, be it a

totalitarian dictatorship or a national leader espousing Marxist ideology.

Even left-leaning US citizens – intellectuals and idealists – were

uniformly branded as enemies of the state, a collective threat to national

security. Until 9/11, terrorism had a much lower profile. |

||

When Timothy McVeigh blew up the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, killing 168 people, the US did not reorganize the federal government or resort to deficit spending just to stem the tide of domestic right-wing extremism. |

At one time, groups led by the likes of Carlos the Jackal, Abu Nidal or even Osama bin Laden were but criminal gangs pursued by law enforcement agencies; they had not yet been lionized as global powers of their own right, befitting a defending nation’s full military engagement. Often they were mercenaries, serving despotic regimes in Tripoli, Damascus and Tehran. Or, like the Abu Sayyaf or the FARC, they were simply racketeers, kidnappers and traffickers whose political agenda were vague and irrelevant. When Timothy McVeigh blew up the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, killing 168 people, the US did not reorganize the federal government or resort to deficit spending just to stem the tide of domestic right-wing extremism. (The radical right themselves would believe otherwise; McVeigh thought he was exacting revenge for the raid by federal agents against the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas a year earlier.) Perhaps it was the fortuitously

swift arrest of McVeigh that averted such a grand response. Perhaps we

were reluctant to admit being victimized by our own native sons. Had we been just as ardent to trace and isolate the extreme

right as a potential threat, as we blacklisted our own communists during

Joe McCarthy’s time, John Ashcroft’s dire vision of an American police

state would not seem so out of place. Since 9/11, that is exactly what the

federal government is trying to do with Arabs in the US, be he an American

citizen or not. |

|

|

There probably wouldn’t be a War on

Terrorism now if al-Qaeda had attacked just another barrack, embassy or

warship stationed in a faraway place. For any family who had to bear the

loss of a loved one, the deaths in downtown Manhattan, the Pentagon and

rural Pennsylvania on that day in September were just as tragic as those

perished aboard the USS Cole in Yemen, the American embassies in Nairobi

and Dar es Salaam, or in the jungles of south Philippines. Beyond that, a

new chapter in world history was indelibly prefaced with the image of the

collapsing Twin Towers, rendering the entire skyline of New York a

poignant memorial. The Cold War is long over; the War on

Terrorism has just begun. Whatever comparison one can make between these

two conflicts, perhaps the most sobering is a count of casualties. On September 11, 2001, 3,748 people died at the World Trade Center, 189 in the Pentagon, 44 aboard Flight 93 in Pennsylvania. There are 58,178 names inscribed on the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington. Charles Weng, 25 August 2002 |

||

| "A Testament Against Terror": Immediate reactions to the 9/11 attacks | |

| Travelogue Title Page | |

| Index |